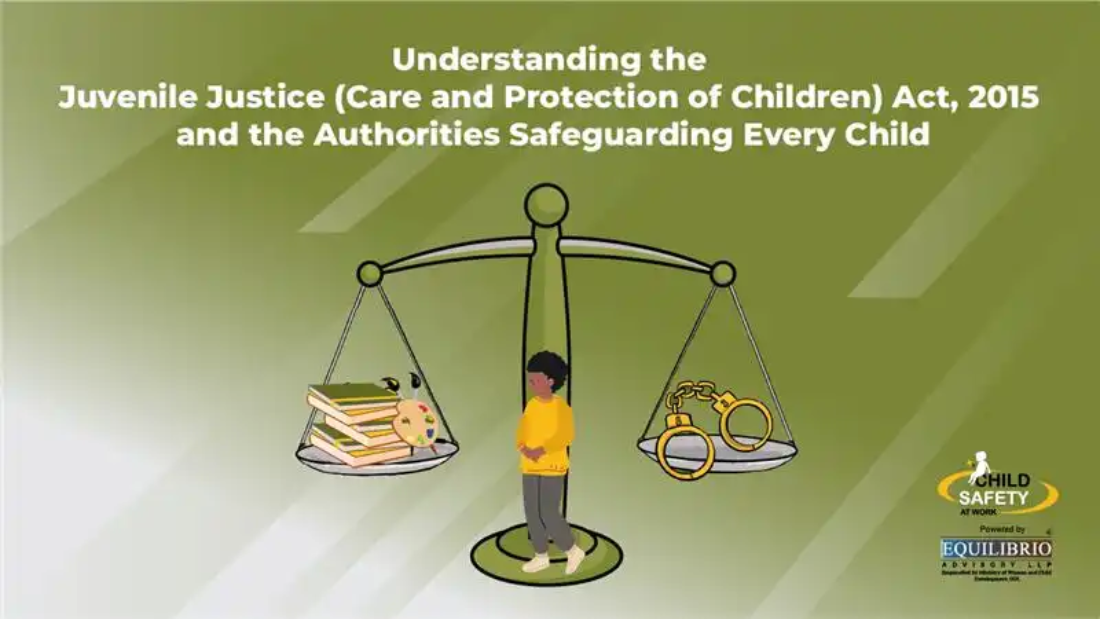

At a busy traffic signal, a child weaves between cars selling trinkets under the harsh afternoon sun. A few streets away, another child is caught by police for snatching a mobile phone from a passer-by. On the surface, the two situations appear very different. One is shaped by poverty, the other by an act that violates the law. Yet both children fall within the protective ambit of the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015 (JJ Act).

The first is a clear case of a Child in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP), whose rights to safety, education, and development are at risk due to neglect and exploitation. The second is a case of a Child in Conflict with Law (CCL), who, despite having committed an offence, is recognised by the law as someone capable of rehabilitation and reintegration rather than punitive incarceration.

Understanding how the Juvenile Justice Act addresses these two situations requires moving from theory to statutory provisions and then to the specific mechanisms of protection, rehabilitation, and accountability.

Why These Children Need a Distinct Legal Response?

Child protection theory recognises that children’s development is deeply influenced by their environment, relationships, and opportunities. The ecological model of child protection explains that harm to children can result from individual, family, community, and societal factors. Poverty, abuse, lack of education, peer pressure, and systemic neglect can push children into vulnerable situations or conflict with the law.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), which India has ratified, requires member states to treat children in conflict with the law differently from adults and to ensure that children deprived of parental care are given special protection. The JJ Act operationalises these commitments in the Indian context by recognising the distinct developmental needs of children, their capacity for change, and society’s obligation to protect them.

Overview of the Juvenile Justice Act and Its Key Definitions

The Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015, is India’s primary legislation for children alleged to be in conflict with the law and those in need of care and protection. The law consolidates provisions for their care, protection, development, treatment, and rehabilitation through child-friendly procedures.

A Child in Conflict with Law (CCL) is defined as a person below eighteen years of age alleged or found to have committed an offence. The Act prescribes a separate system of inquiry, trial, and rehabilitation for such children through the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB).

A Child in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP) is a child who is found without any home or settled place of abode, or whose parents are unfit or unable to care for them, or who is found working in contravention of labour laws, begging, living on the street, subjected to abuse, or at risk of early marriage, trafficking, or other harm. These children are produced before the Child Welfare Committee (CWC) for protective measures.

These definitions are crucial because they trigger the legal obligations of authorities and stakeholders under the Act.

Mandatory Reporting

One of the most significant features of the JJ Act is the obligation of mandatory reporting under Section 31. Any person, organisation, or institution that comes across a child who appears to be in need of care and protection must report the matter to the CWC , local police, ChildLine services, or other designated authorities.

Failure to report can lead to penalties, as the law treats silence or inaction as enabling harm. This provision recognises that early intervention can prevent further exploitation, abuse, or criminalisation.

For example, if a shopkeeper regularly sees a child at the traffic signal selling goods during school hours, they have a legal obligation to alert the authorities. Similarly, if a teacher suspects a student is engaging in petty theft due to coercion by older peers or family members, they must report the situation so that protective measures can be taken.

Mandatory reporting is not merely a procedural formality. It is the first link in a chain of protective action, setting in motion inquiries, rescue operations, rehabilitation planning, and monitoring to ensure the child’s safety and well-being.

Authorities Under the Juvenile Justice Act

The JJ Act establishes several specialised authorities to implement its provisions. Each has a distinct constitution, composition, and set of duties.

Juvenile Justice Board (JJB): The JJB deals exclusively with cases involving children in conflict with the law. It consists of a Metropolitan Magistrate or Judicial Magistrate of First Class, along with two social workers, at least one of whom is a woman. The Board conducts preliminary assessments in cases involving children aged sixteen to eighteen accused of heinous offences and decides on rehabilitation or trial as an adult in the rarest cases. Its role is not punitive but reformative, ensuring that children receive counselling, education, and skill development opportunities.

Child Welfare Committee (CWC): The CWC is the final authority for decisions regarding children in need of care and protection. It comprises a Chairperson and four members, at least one being a woman and another an expert in child health, education, or welfare. The CWC has powers to direct the placement of a child in a fit facility, order medical treatment, initiate adoption processes, or restore the child to family care if safe. It is mandated to operate in a child-friendly manner, focusing on the child’s best interests.

Special Juvenile Police Unit (SJPU): Every district must have an SJPU headed by a police officer not below the rank of Deputy Superintendent of Police, with officers trained in child rights and protection. The SJPU’s duties include receiving children from police stations, producing them before the JJB or CWC, ensuring their safety during custody, and collecting evidence in a sensitive and child-friendly manner.

District Child Protection Unit (DCPU): The DCPU functions as the implementing arm of the Integrated Child Protection Scheme (ICPS) at the district level. It is headed by a District Child Protection Officer and includes officers for child protection, legal matters, and counselling. Its duties include mapping vulnerable children, maintaining records, coordinating with NGOs, ensuring the functioning of CWCs and JJBs, and managing funds for child welfare schemes.

State Child Protection Society (SCPS): The SCPS oversees child protection policies and programmes at the state level. It provides technical support, develops guidelines, trains personnel, and monitors the functioning of CWCs, JJBs, and other childcare institutions. It ensures that state-level schemes are aligned with the JJ Act and that data on children is regularly collected and analysed.

Childline Services (1098): Although operationally run by NGOs, Childline is an integral part of the JJ Act framework. It provides a 24-hour toll-free helpline for children in distress. Calls are referred to the appropriate authority such as police, SJPU, CWC, or DCPU for immediate action. Childline workers also follow up to ensure that the child receives necessary support.

Fit Facilities and Fit Persons (Section 51 & 52): The Act allows the CWC or JJB to place children with individuals or institutions deemed suitable for their care and protection temporarily. A fit person is an individual assessed for their ability to provide a safe environment, while a fit facility is an organisation meeting prescribed standards for childcare.

Linking the Scenarios Back to the Act

In the CNCP example of the child selling toys at a traffic signal, mandatory reporting would trigger the involvement of the SJPU or Childline, leading to the child’s production before the CWC. The CWC would order a Social Investigation Report, assess the child’s needs, and decide on rehabilitation measures, which could include shelter, education, healthcare, and family counselling.

In the CCL example of the child involved in theft, the police would refer the case to the SJPU, which would produce the child before the JJB. The JJB would inquire into the circumstances, provide legal aid, and design a rehabilitation plan, possibly involving community service, vocational training, or counselling, while avoiding incarceration unless absolutely necessary.

In both cases, the aim is to prevent further harm, address root causes, and reintegrate the child into society in a safe and supportive manner.

The Role of Stakeholders in Child Protection

While the JJ Act sets up the legal and institutional framework, its success depends on the active participation of stakeholders who interact with children daily. Parents, teachers, healthcare workers, social workers, police officers, and community leaders are in a position to notice early signs of vulnerability or conflict with the law.

Schools, in particular, play a crucial role in prevention and early intervention. Teachers can spot behavioural changes, absenteeism, or unexplained injuries and can act as first responders by reporting concerns to the appropriate authorities.

To strengthen this role, we have developed a specialised e-learning module for schools on the Juvenile Justice Act. This module covers recognising risk factors, understanding reporting procedures, and working with child protection authorities. Stay tuned for its launch so together we can ensure that every child is protected, supported, and given the opportunity to thrive.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1. What is the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection of Children) Act, 2015?

It is India’s main child protection law safeguarding Children in Conflict with Law (CCL) and Children in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP).

Q2. Who are the authorities under the Juvenile Justice Act?

Authorities include the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB), Child Welfare Committee (CWC), Special Juvenile Police Unit (SJPU), District Child Protection Unit (DCPU), State Child Protection Society (SCPS), and Childline 1098.

Q3. What is the difference between CCL and CNCP?

CCL are children below 18 accused of an offence; CNCP are children who are abandoned, abused, trafficked, exploited, or neglected.

Q4. What is mandatory reporting under the JJ Act?

Anyone aware of a child at risk must report it to the CWC, SJPU, police, or Childline 1098, failing which penalties apply.

Q5. How does the JJ Act ensure rehabilitation of children?

It provides counselling, education, foster care, adoption, and reintegration instead of punishment.

Q6. What role do schools and teachers play under the JJ Act?

Teachers must report neglect or abuse and support children’s safety, education, and rehabilitation.

Q7. What is the Juvenile Justice Board (JJB)?

The JJB handles cases of children in conflict with law and focuses on reform, not punishment.

Q8. What is the Child Welfare Committee (CWC)?

The CWC is the final authority for children in need of care and protection and decides on shelter, family restoration, or adoption.

Q9. What is Childline 1098?

Childline 1098 is a 24-hour toll-free helpline that rescues and supports children in distress.

Q10. What are fit facilities and fit persons under the JJ Act?

They are approved individuals or institutions deemed safe for temporary care and protection of children.

Written by Adv. Deeksha Rai Reviewed by Adv. Farzeen Khambatta and Rosanna Rodrigues

Cart is empty

Cart is empty